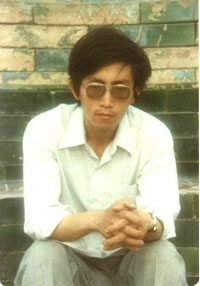

Bei

Dao

in conversation with Michael March

The importance of being ”ordinary”

Bei Dao - north

island - is the pen name of Zhao Zhenkai, a singular figure who many

consider to be the finest poet in China. He was born in Beijing in 1949.

The outbreak of the Cultural Revolution ended his formal studies in 1966.

He joined the Red Guards but soon lost enthusiasm for the movement. In

1969 he was assigned to work in a construction company in Beijing. Unlike

many of his generation, he was not 'sent down' to the countryside. He

participated in the Tiananmen Incident of 5 April 1976, demonstrations

which became the symbol of resistance to the Gang of Four and the dictates

of the Cultural Revolution. The events inspired The Answer, his most

famous poem. "I don't believe that death has no revenge."

Bei Dao - north

island - is the pen name of Zhao Zhenkai, a singular figure who many

consider to be the finest poet in China. He was born in Beijing in 1949.

The outbreak of the Cultural Revolution ended his formal studies in 1966.

He joined the Red Guards but soon lost enthusiasm for the movement. In

1969 he was assigned to work in a construction company in Beijing. Unlike

many of his generation, he was not 'sent down' to the countryside. He

participated in the Tiananmen Incident of 5 April 1976, demonstrations

which became the symbol of resistance to the Gang of Four and the dictates

of the Cultural Revolution. The events inspired The Answer, his most

famous poem. "I don't believe that death has no revenge." His national emergence in China

dates from his decision to co-edit and publish Jintian (Today), an

'unofficial' literary journal which first appeared as a big character

poster on Democracy Wall in 1978. though seen as heir to the "PShadow

Poets", the young poets loosely attached to the Democracy Movement, Bei

Dao remains self-possessed. "Poets should established through their works

a world of their own, a genuine and independent world, an upright world, a

world of justice and humanity."

After the Cultural

Revolution was there a

longing to return to classical Chinese roots? The Tao Te Ching

says that "the longest way is the way back".

This is a philosophical problem, perhaps related to a

poem of mine called Returning To My Home City. For me, "the way back home"

has many layers of meaning. one meaning is the return to

the original location of my life, to the source of my life. And

if that is what is meant, then it is a very long road.

O am less concerned by the idea of returning to the origin

of Chinese culture. This too is a very long road, but

it is not a road that I want to return to. Many Chinese poets have

made the return on this road. Originally, they wanted to leave it.

But in the end, they returned.

Why?

It's a very complex topic. If I simplify it - the

history of Chinese culture is so long, we have many splendid achievements

- it has a very strong attractive power. And a particular

feature of Chinese culture is its closed aspect, the fact

that it's a closed system. It is very easy to rely on

this cultural system. That's why, ever since the Fourth of may Movement, many

Chinese poets who intended to write new poetry, to start again, have,

in the end, returned to traditional poetry.

Now you find yourself in Durham. What are your impressions having

spent a year in the West?

I talked with a friends about this. I said that if

I'd been out of China for just a week, I could have written a book. If I'd

been out for a month, perhaps I could only have written an essay. Now that I've been here for

over a year, I think I won't be able to produce anything at

all. Of course, the cultural differences are great, but sometimes I feel

we should forget these differences and look at ourselves in a

new way. I have found a real sense of being on my own.

The road that I talked about, the road back, is the road to the origin

of myself, my life. I think that I suffered a misapprehension about myself,

in that I had been influenced, within my own thoughts,

my own feelings, by society's attitudes. In China you're

always being criticised or being praised. Both have a malign

influence. Here, I have realised the importance of being an ordinary person. The

most important thing is living your own life.

But can a poet be

ordinary?

First of all you should be an ordinary person. What

are you afterwards, I don't mind.

The Party in China would agree with you. They would

say that everyone is ordinary, sharing a common base. But what your

generation in China saw in your poetry was precisely your very personal

voice.

In China's dark period I wanted to express some opposition, but I didn't

feel that I was representing anybody. I don't agree with

the idea of representing people. I don't agree with

the idea of people representing others.

Why has your poetry been so popular with students,

with the younger generation in China?

I think there are two aspects to this. My poetry is a

voice of truth. So in a society filled with lies, it is possible to find something real

in it. But many young people misunderstand. They want to find a way

to get rid of their frustrations. I remember once in

Sichuan. We were holding a reading. Several thousand people had come, so

they burst down the doors. We were treated like pop stars

at pop concerts in the West. I am rather suspicious of this. Poetry is

a minority occupation. their interest was a political interest. Although

I understood their feelings, it was regrettable, a misunderstanding on their

part.

If we live in a society

which lies to us, how do

we overcome the lies, how do we find truth to express

ourselves?

That's a very difficult question to answer. Of

course, you should respond to lies with truth. But sometimes you find in

your own voice a flavour of falseness, a touch of falseness even though

you want to be true. It is very difficult

to find a method, a way in which to oppose

lies.

In a statement about poetry

you said: "Perhaps the whole difficulty is only

a question of time and time is always just." is time just,

now that you're an "old man"?

It is a fine hope. As a man lives between

hope and despair, so he lives between conspiracy and

judgement.

In‘ The Answer’ you speak of coming into this world "To

proclaim before the judgement / The voice that has been judged". ‘The

Answer’ is a very political poem. But to what extent can you find

political freedom, as opposed to personal freedom, within

poetry?

I hope to find a certain freedom as a poet and I

hope to find a certain freedom as a person.

The poets of your generation

- those that emerged after the Cultural Revolution, out

of the Democracy Movement - are known as the "Shadow Poets"

or the "Misty Poets". Is there such a

phantom?

This concept of the "Misty Poets" is very vague. It

was originally a term of criticism used

by others. We had no choice but to accept this

name. It doesn't really refer to a literary group, a literary

movement. We were pushed together through political pressure.

Your generation came as an explosion in China. How

did that explosion come about?

There was a direct connection with the Cultural

Revolution. For thirty years prior to the Cultural Revolution, Chinese literature,

particularly poetry, was a vacuum, a territory of lies. Though the

Cultural Revolution was a disaster, it marked a turning

point. Perhaps you can express it as an earthquake, opening up

a new age.

What spirit

emerged?

Culture has its own fundamental origin. Young people

started to look critically at their own culture. They discovered that the Cultural Revolution wasn't only a

political movement. They attempted to find an answer to history.

The initial point about the new literature was respect for individual

rights. For Westerners this is seen as something in the

past. For us this is seen as fundamental. For several thousand years

in China, individual freedom has been very deficient. So this was an

important beginning.

What was your direct

experience during the Cultural

Revolution?

From first to last I took part in all its activities.

I came from an ordinary household, so I suffered from a certain amount of

pressure at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution. I didn't

come from one of the higher-level households. So I took part

in the Red Guards. I traveled a lot. I joined in

the fights between different cliques, took part in things which could be

called criminal activities. In the first stage after the Cultural Revolution,

people were looking for the villains, the people who

perpetrated the crimes in this so-called "scar literature". The problem

is that everybody was a victim. So who were the villains, who were the

perpetrators? there was a turning point in literature when people discovered that

it was all up to them; they couldn't blame someone else. Where did

one's own criminality come from? Many young writers are searching

history for an answer.

Did the Tiananment Square incident lead to the

founding of the literary journal, ‘Today’?

It was a political opposition movement, a democratic

movement, a movement which was asking for democracy. But its goal was very

vague. By the end of 1978, those involved began to understand their goal:

democratic freedom and the restoration of basic rights. Today and the

Democracy Movement had a close relationship, but they weren't completely

the same thing. In the final analysis, Today was a literary movement. Its

history starts much earlier than the Democracy Movement. It stems from the

early seventies, a time when many young people were engaged in underground

writing. Today became their

public voice. It was very close to the political atmosphere not existed,

it would have been impossible to publish the

magazine.

Was Chinese writing isolated or did this ferment

come from the events of 1968, from Western influences?

You could say, in a way, that 1968 was a

result of the influence of the Cultural Revolution.

In ‘Tomorrow, No’ you say "whoever has hopes

is a criminal”. Does that mean Mao as well as everybody is a

criminal?

It is still very difficult to evaluate Mao. He was

a good poet. But his crazy ideas - he put his crazy ideas

into political effect. Finally, it was a terrifying phenomenon.

Are both politicians and poets

crazy?

The mode of their craziness is different. When politicians go crazy,

they want to force their ideas on others. Poets decline the

honour.

When I asked a Russian poet why poetry

is so popular in the Soviet Union, she said ”because it's science

fiction”.

Who knows? Perhaps it's because of the particular literary tradition of reciting poetry,

of starting a relationship with a reader.

Is poetry popular in

China?

In the past few years it's been very popular. But as

I've said before, the reason rests

with its connection to a political movement. Now its status suffers the

same fate as that of poetry in the West.

What is your experience of literature in

Western societies?

Very good. I dislike poetry as propaganda. In a society where politics tries to

control literature, even opposition is a sort of propaganda. Basically, this

problem doesn't exist in the West. Of course, there are

problems between political parties and between classes. A Western writer said

the reason the Soviet Union imprisons its writers is because

it regards them so highly. Whereas in the West, they are hardly

noticed.

Do you feel

in exile or suspended animation living in the West?

Who wants to exile me? You can call

this self-exile. I hope this period will be short. I don't anticipate

staying for a long period in the West.

In recent years a number of

Chinese poets have been able

to go abroad. What do you think motivates them to

travel?

Each person has a difference reason. Poets need to experience life, to draw

comparisons. It's very good thing if a poet can get

out.

In ‘The Comet’ you said: "come back and we'll rebuild

our home or we'll leave forever like a

comet."

Rebuilding is always a dream, but poets need to rely

on this dream.

In ‘All’ you said: "all deaths have

a lingering echo." Is poetry near death?

Poetry is very close to both life and death. Poets have

a fear of life and death. This becomes a motivation for writing. Poets try

to find a balance between life and death. But this balance is

very difficult to control, because the boundary, this line, is very

narrow. So it's easy to fall off. Many good poets choose

suicide.

Why?

They haven't yet maintained the balance. But many

bad poets choose life. They fall on that side of the

balance.

"When souls display their true form in rock,

only a bird can recognize them," you say in

‘Daydream’.

This is talking about living between reality and

unreality in life. When I'm talking about daydreams,

I am talking about everyday life. I am trying to

express my perplexity in everyday life. It's describing the state of perplexity

in which I live.

Also in ‘Daydream’, you say

"light comes from a pair of

copulating eels at the bottom of the sea." Do you read at night by this

light?

It's not for reading. It's for writing.

Index on Censorship October

1988